Background

As a high school student, finding love can be hard. Similarly, finding people willing to spend their weekend teaming up with me at a hackathon can be hard as well.

At hackCooper 2016, I worked with Isabella Berry to solve these two problems with Github Dating Simulator, an application that analyzes compatibility between Github users by using graph theory and the power of love. It’s not a dating simulator in the traditional sense—rather, it’s a web application that allows people looking for hackathon teams to find people with similar coding backgrounds to avoid the hassle of scrambling to find a team at the last minute.

Overview

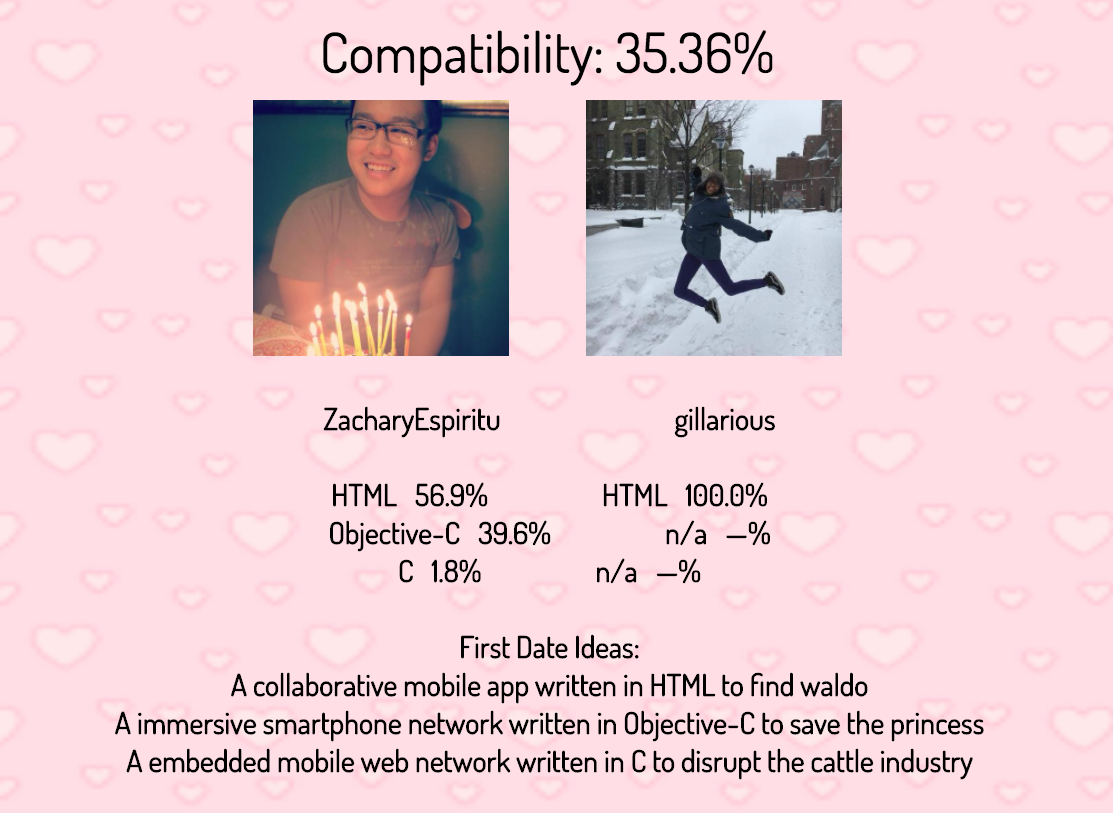

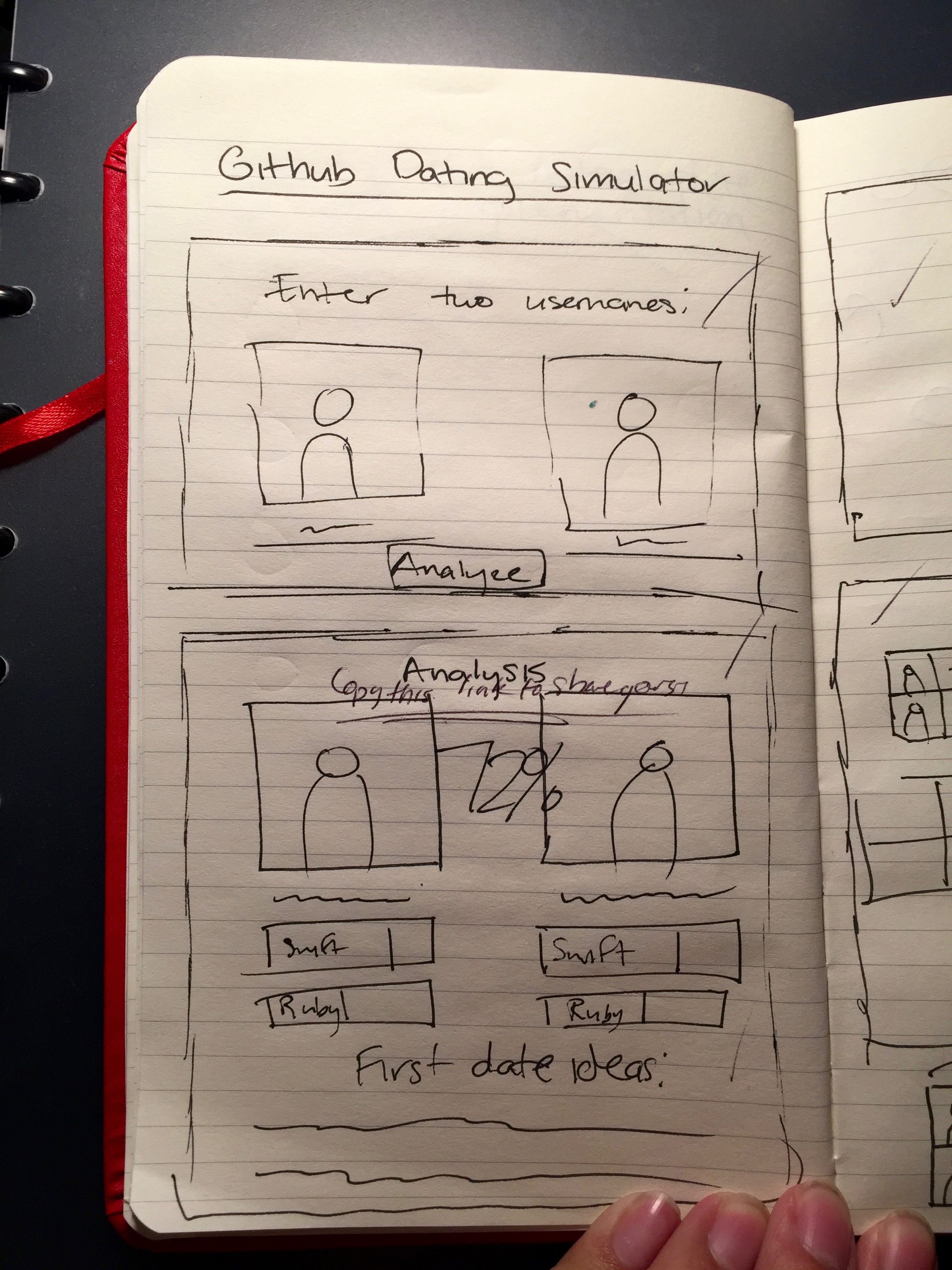

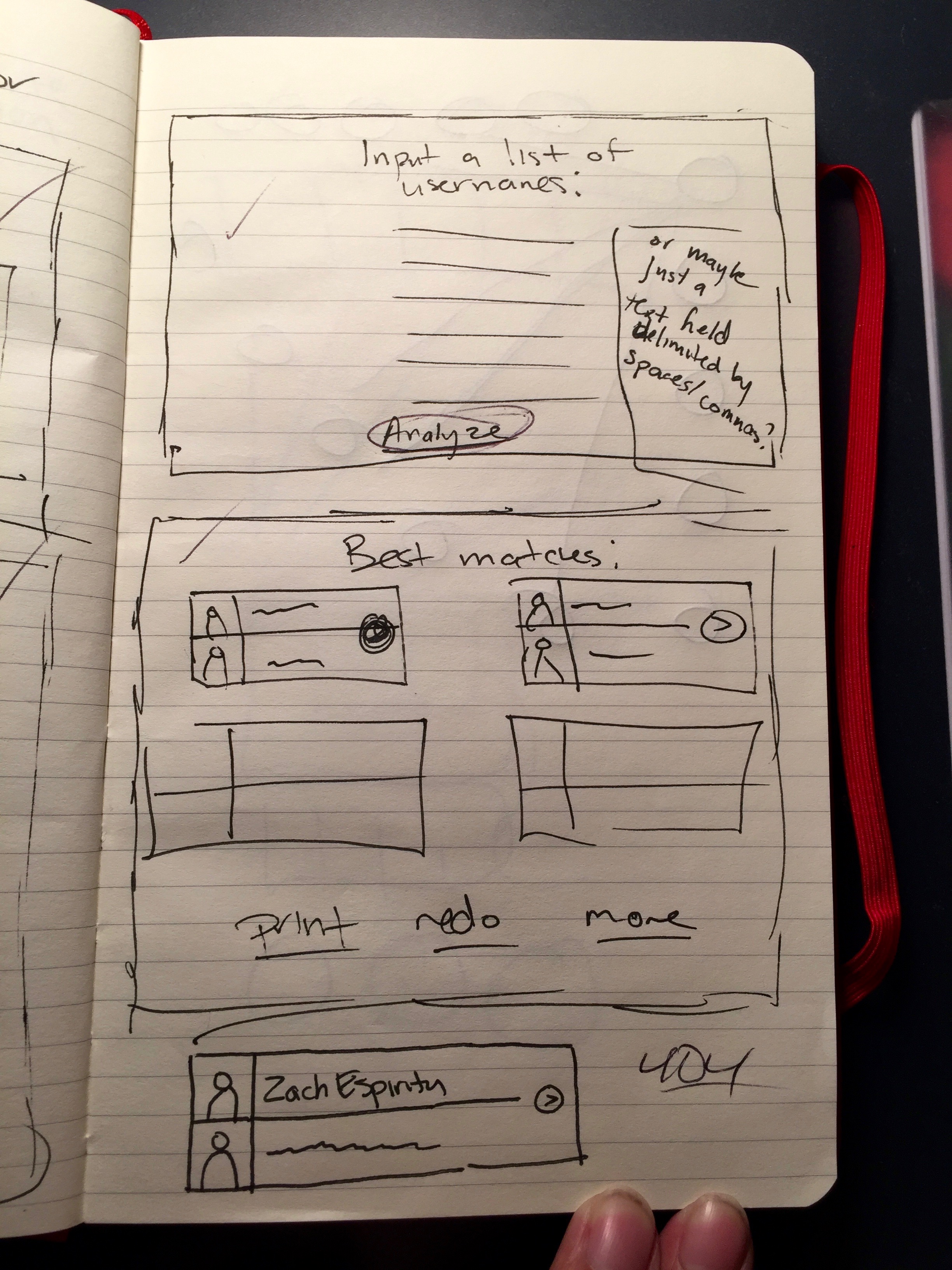

Github Dating Simulator comes in two flavors. “Dating mode” allows a user to input two Github usernames to determine how compatible they are. “Team generation mode” (the more practical mode) allows a user to input a list of Github usernames, will return the best possible pairings for each of the users. It also allows them to set several options, such as how many people should be included in each team.

For every match that Github Dating Simulator analyzes, it outputs a “compatibility” percentage, which is essentially the program’s confidence level that these two people will be able to work together well.

Just for fun, it also generates a list of “first date ideas”, which are essentially randomly generated project ideas based on the common languages shared between each user to help kickstart the ideation process. (And when it finds very compatible matches, it also outputs a list of “first date locations”—a.k.a. upcoming hackathons.)

Implementation

I was responsible for the UI design and the technical implementation on this project. Perhaps one of the most statistically intensive projects I’ve worked on so far, Github Dating Simulator relies on a combination of the Github API and graph theory-based algorithms to efficiently and accurately pair users.

To create matchings, it looks at the language usage of each user and compares it on an experience-based level to those of the other users. This means that a person who has a lot of repositories written in Ruby will be marked as an “expert” while someone who only has only written 70 lines of Ruby will be marked as a “beginner”. This allows users to be matched with other coders proportional to their skill level, which allows coders to work with people of similar coding backgrounds, making for a much easier hackathon experience overall.

(This is something that was highly contested, as one might want to match people with more experiences with certain programming languages with those who have less experience for a more educational experience. Perhaps an option for such a matching algorithm will come in a future update.)

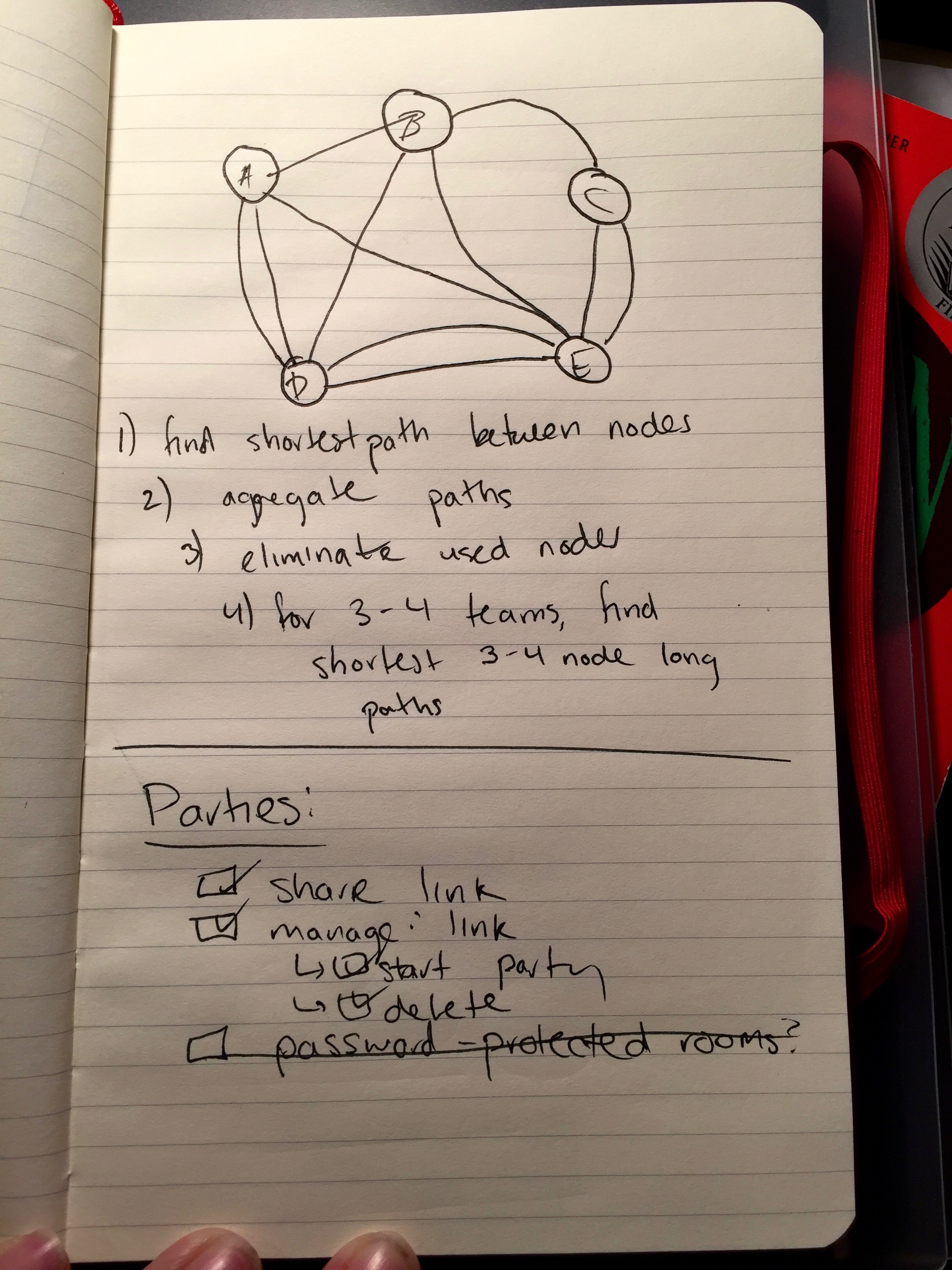

On a graph, each user is plotted from other users with different paths of varying “lengths”. Each user is a node on the graph, and each path represents a common language between two users. (If two users do not share any common languages, they will not have any paths between them.) Path length is calculated by the mean square difference of each of the languages a user knows.

The algorithm tries to find the shortest path (essentially, similar experiences with certain languages) between two users. It then aggregates all of the paths between two users into a single “compatibility” metric based on a logarithmic scale, and then begins creating matches starting from the highest compatibility percentage. Once a user has been matched with another user, it will delete both users from the graph so they cannot be matched again. The algorithm continues until all users have been matched or there are no more available users to match.

One of the major challenges that we ran into was that the Github API has rate limiting, which prevents one from making too many API requests in a given time frame. To solve this problem, we implemented a pseudo-caching mechanism with a PostgreSQL database. Using the Github API’s conditional request feature, we only make a full request to Github if they tell us that the data at each location has been changed. Otherwise, we simply rely on previously stored data since we know that it hasn’t changed.